Forty-one years ago in New York City, a man known only as Simon walks into a witchcraft supply shop with a cardboard manuscript box, the kind of thing you see in library rare book departments. He estimates that the work in his possession is six or seven hundred years old.

Simon is a Slavonic Orthodox priest, a student of the occult, but until he walked into that shop he didn’t know anything about H.P. Lovecraft, a writer of “weird fiction” (the literary forefather of both science fiction and horror). Neither had he heard of the Necronomicon, a book that the author had invented for his stories. It’s supposed to be an incredibly powerful grimoire, or collection of spells and incantations, and as Lovecraft was in the habit of blending reality and fantasy in his books — even going so far as enlisting other “weird” writers to expand on his characters and locations in their own stories — more credulous readers came to believe that the Necronomicon was real. It was as if Luke Skywalker was real, or the flying skateboards from Back To The Future were real.

Magickal children

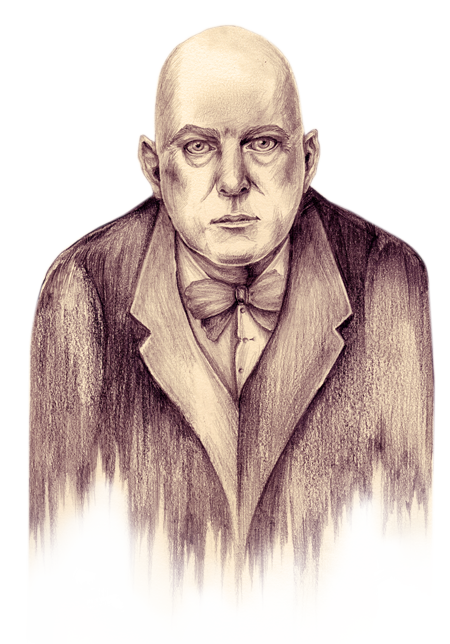

The store was called The Warlock Shop and the owner was Herman Slater (later it would move from Brooklyn Heights to Manhattan and change its name to The Magickal Childe). Slater was a large, gay witch, and something of a living legend in occult circles. On this particular day, as Simon would later write in his book Dead Names: The Dark History of the Necronomicon, the air was thick with the smell of incense and Slater was dressed in a ceremonial robe with the hood pulled over his head, “like a character actor from the old film Horror Hotel.” The heavy-handed drama of the account suggests a creation myth in the making.

Simon and Slater dig into the old, faded manuscript, a magical curiosity.

“What does it say on the first page?” Slater asks, “does it have a title?”

Yes it does, replies Simon. But he has no clue what it’s supposed to mean.

“The first word, here,” he tells Slater, “is a Greek word, ‘necronomicon.'”

“You’re full of shit!”

Slater was right to be skeptical. In the years between Lovecraft’s death in 1937 and that day in 1972 when Simon brought him the manuscript, there had been several attempts to bring Lovecraft’s Necronomicon to life — but these books were always understood to pay homage to Lovecraft. But the Simon Necronomicon was an actual magical document that Simon claims predated Lovecraft’s stories by several hundred years. If real, it would mean that Lovecraft’s stories weren’t entirely fictional, after all.

Henry Slater wanted that book. Until Simon walked in with that cardboard box full of brittle, decaying paper, Slater had a jar of dirt from a graveyard, he had incense and candles, magical weapons, and bat’s wings. But he didn’t have a Necronomicon.

“If he could list a Necronomicon in his catalogue,” wrote Simon in Dead Names, “he would make a fortune.

Portrait of the artist as a young misanthrope

H.P. Lovecraft was a strange bird, indeed. He was tall and skinny with a large, protruding chin — perhaps resembling a walking caricature of himself. His stories have been criticized for only hitting one chord: a long, droning, minor chord that instills an immense feeling of dread in the reader. He wasn’t a “hack,” he wasn’t writing merely to write, or to make a buck — even if he did make that claim on occasion. When you read his stories, at times it feels as if you’re probing some very dark places within yourself. Joyce Carol Oates once likened his writing to “a form of psychic autobiography.” His life was shot through with the belief that, as Lovecraft once wrote in a letter to one of his editors, “common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.”

“Common human laws and interests and emotions have no validity or significance in the vast cosmos-at-large.”

He died in 1937 virtually unknown, but his fame has grown remarkably since then. Not only is his influence felt in literature and film, but in the occult world as well. By the 1970s it was inevitable that if the Necronomicon never existed, one would have to be invented. And over the years, there have been several: a couple as hoaxes, and a few that paid artistic homage. When Slater saw what Simon had brought in, he immediately knew the book would be a success, and potentially quite profitable. He introduced the priest to a publisher named L.K. Barnes, and in 1977 the first edition of the Necronomicon, “edited” by Simon, was released. It’s been in print ever since.

I was in Providence recently, the city of Lovecraft’s birth and the place where he lived practically his entire life. While I was there, I spent a night in the Biltmore hotel. I was attracted both by the fact that it appears in a story by H.P. Lovecraft as well as by the rumor that it was haunted. As it turns out, it isn’t haunted at all — it’s just a dump.

From the Biltmore, it’s a pleasant 40-minute walk to the home that Lovecraft shared with his mother on Angell Street. When I stopped by to check it out, the front door was wide open and a large white dog was tied up in the doorway, ears at attention. I could make out a bookshelf inside, but the hound wouldn’t let me get close enough to read any of the titles.

When he lived in this house a century ago, Lovecraft was 23 years old, nearing the end of what his biographer Donald Tyson calls a “five-year withdrawal into solitude,” precipitated by nervous collapse that occurred during his senior year in high school. He dropped out of school and, as a result, he had to face the fact that he’d never be an astronomer, he’d never be a professor at Brown University.

“It is difficult to adequately describe how antisocial Lovecraft was at this stage in his young adult life,” writes Tyson. “For five years he lived in almost complete solitude with his conceits, affections, and prejudices.” It was also at this time when his affections switched from studying science to reading and writing weird fiction. He was encouraged in this regard by a group called the United Amateur Press Association, a group of amateur writers that pooled their resources and printed their own magazine, United Amateur. It was this outlet that eventually helped him ease out of his nervous breakdown. “I obtained a renewed will to live,” he later wrote, “and found a sphere in which I could feel that my efforts were not wholly futile.”

He immediately knew the book would be a success, and potentially quite profitable

And soon, people would read his stories — full of supernatural godlike entities from outer space and ancient times — and begin to see them as mythology. Some would even go so far as to speculate as to whether someone could produce writing so meaningful to them without being a magician or psychic medium themselves. Of course, Lovecraft was a strict materialist. One who died with little knowledge of the occult, and who certainly didn’t believe in magic.

Tyson, author of The Dream World of H.P. Lovecraft, explained to me recently that the answer to this paradox lies in the fact that Lovecraft’s stories were often based on his dreams. “I think that when Lovecraft was asleep,” said, “he projected himself astrally to various astral realms.” His dreams, in other words, were astral projections.

“The astral world was important to Lovecraft, even though he didn’t know it.”

Tyson specifies a number of Lovecraft stories that he says are based directly on his dreams or which concern dreaming as a central theme. It was one of these dreams that inspired not one but two stories: “Dagon” and what is probably Lovecraft’s most well-known work: “The Call of Cthulhu.”

In “Cthulhu,” the narrator investigates a “voodoo cult” believed to be behind the disappearance of women and children near New Orleans. They worship a group of deities known as the Great Old Ones, “who lived ages before there were any men.” Cthulhu is a monster “with an octopus-like head whose face was a mass of feelers, a scaly, rubbery-looking body, prodigious claws on hind and fore feet, and long, narrow wings behind.” The cultists, according to the narrator, are little better than animals themselves, being “men of a very low, mixed-blooded, and mentally aberrant type.” He includes in this group “a sprinkling of negroes and mulattos, largely West Indians or Brava Portuguese from the Cape Verde Islands.” This is in line not only with Lovecraft’s weird racist streak, but also with the cold, rationalist perspective that reduces people to the status of mere animals.

Before leaving Providence, I paid a visit to Lovecraft’s grave in Swan Point cemetery, where a friend and I found the family plot without too much trouble. It wasn’t even until 1977 that he had his own grave marker — for the first 40 years after his death, he made do with an addendum to his parents’ monument. Even in death he can’t get away from his mother. Scattered around the small, unassuming grave marker lay a number of items, including guitar picks, a ticket stub for a concert by a Swedish black metal band called Watain, and the business card of a Toronto-area magic shop.

There was also a handwritten note that read:

THANK YOU H.P.

YOUR WORK LIVES

ON — YOUR VISIONS

BEAR FRUIT +

WE ALL CREATE

IN YOUR SHADOWW.C.

PS. YOU WERE WRONG ABOUT THE PORTUGUESE PEOPLE, THOUGH

Intern of The Beast

The first mention of the Necronomicon was in April 1923, when Lovecraft submitted “The Hound” for publication. In this short story, the book is mentioned briefly, as a sort of reference book for grave robbers. (“What is that creepy amulet, anyways? Check the Necronomicon!”) Until his death, Lovecraft would continue to develop the idea of the book, as would the other members who made up what is known as the “Lovecraft Circle,” a group of writers who all corresponded with each other and who used elements from Lovecraft’s stories in their own, creating a shared fictional universe.

Lovecraft’s posthumous fame began in the 1960s and really took off in the 1970s, coinciding with both an Aquarian Age hunger for all things otherworldly and the introduction of mass-market paperback collections of his stories. As his audience increased, so did the desire of fans to possess a Necronomicon of their own. When Simon’s Necronomicon finally hit the shelves, it must have seemed as if Lovecraft’s universe had cracked open and spilled its contents all over New York City. At the time, Simon was also conducting workshops on occult subjects in the backroom of The Magickal Childe. Among those who couldn’t resist coming to get a better look at the man responsible for the Necronomicon were two young men who would go on to become key figures in the burgeoning field of Lovecraft studies: S.T. Joshi and Robert M. Price.

Simon, though still in his 20s, had an aura of mystery and authority. “He was a younger man than I would have expected,” says Price. Simon was formally dressed. He was rocking “black hair and a goatee.” When asked about his impressions of the evening, he draws a blank. “It wasn’t that exciting.” Joshi had the same impression, which he shared with me recently: “I don’t even remember what he said.”

It’s likely that he heard something like this:

Anyone considering becoming involved … in the occult practices which form the greater part of the Necronomicon must first realize that this is first of all a work of Ancient Sumerian religion. That is to say, these practices predate both Judaism and Christianity by thousands of years …

We’re speaking about a very ancient, and possibly very potent form of ceremonial magick.

The above passage is taken from a tape called “Simon Says,” a lecture credited to the occultist and priest that’s available on the internet as a bootleg. (It might not be Simon, but it’s sure in line with his spiel regardless.)

Simon’s Necronomicon supposedly has its roots in ancient Sumerian magic. He came across it, the story goes, while on a trip to the Bronx to peruse the wares of two characters named Michael Huback and Steven Hapo who would go on to be busted for hocking books they had stolen from Yale University’s Sterling Memorial Library. As for the few similarities between his book and the Necronomicon of H.P. Lovecraft, Simon contends that they’re purely coincidental. This is supposed to convince us that the Simon Necronomicon is the real deal: why would someone go to all the trouble of fabricating the book and then come up with something completely unlike Lovecraft’s version? As Simon has said himself on multiple occasions: “If it is a hoax, it’s a damn poor one! There is so little there that corresponds to Lovecraft’s oeuvre that it might be embarrassing as a hoax.”

Hoax or not, the Simon book has been in print more or less continuously since 1980, when it was picked up by Avon books after two small press editions. You may be familiar with the thing: it’s a glossy black paperback featuring a magical symbol on the cover and its title printed in capital letters. The whole thing is set off by a garish neon-red border, at once both futuristic and ancient. There’s no author listed on the front cover or the spine of the book. The border, the symbol, and the title all have a lens flare effect added, for some reason. This book has been a classic among freaks, geeks, and Dungeon Masters for decades. The back cover blurb proclaims it “the most famous, the most potent, and potentially, the most dangerous Black Book known to the Western World.”

One occultist who put a lot of stock in Simon’s Necronomicon was Kenneth Grant.

“We’re speaking about a very ancient, and possibly very potent form of ceremonial magick.”

In 1945, a 20 year old Kenneth Grant spent several months working as the secretary for Aleister Crowley, a ceremonial magician, author, mountain climber, and possibly even spy for British intelligence during World War I. Crowley’s books are key texts of modern occultism, and his reputation as “The Wickedest Man In The World” or simply “The Beast” has given him pride of place in any number of heavy metal songs — not to mention a choice spot on the cover of the Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band album (the top left, chilling with Mae West and Lenny Bruce). At the end of his life, Crowley was unable to afford a secretary, so he let Grant fill that role in exchange for magical instruction. For a short while at least, Grant was The Intern of The Beast. By the time he passed away in 2011 at the age of 86, Grant had produced nine volumes that constitute what he called “The Typhonian Trilogies,” which explored the connections between all manner of occult systems — incorporating voodoo and tantra and elements from the work of 20th century magician and the artist Austin Osman Spare.

In turn, Grant’s work is the subject of a recent book by Peter Levenda. The Dark Lord explores the connection between Lovecraft’s writings and modern occultism. In Lovecraft, Grant had found someone with the rare ability to articulate and illustrate the face of evil — which is something that most religious and magical systems gloss over.

“Lovecraft,” says Levenda, “is talking about an aspect of mysticism, of religion that the Golden Dawn was loathe to confront directly,” evil itself. But to be worthwhile, he explains, a magical system “has to be totally encyclopedic. It must represent all of reality … it’s got to represent darkness as well as the light.”

Ultimately, Grant read Lovecraft’s stories and found the work of someone with a very coherent understanding of this darkness. Even if Grant’s idea of magic doesn’t fit into Lovecraft’s universe, he could take elements of Lovecraft’s universe and bring them into his own.

Return of the Ancient Ones

At the Fales Library at NYU, inside the computer-regulated atmosphere of the electronically secured special collections department, there is a document dated April 7th, 1978 and signed by the Beat Generation author William S. Burroughs. It’s title: “Some considerations on the paperback publication of the NECRONOMICON.”

Burroughs, considered shocking and at times dangerous for books like Junky and The Naked Lunch, doesn’t get nearly enough credit for being playful in his work or in his relation to the world. His stories are confabulations of his dreams, his fantasy life, and his real life, woven into something of immense depth and weirdness and black humor. This quality, the idea that you can rearrange the world like a child rearranges Lego-brand building blocks, extended outward from his writing into his everyday life. He believed in magic. He put curses on people, using the same “cut-up” method that he used to compose stories. By cutting a document into pieces, whether a newspaper or something by Shakespeare or his own writing, and reassembling it, looking for a story in the newly remixed document. The results, Burroughs told The Paris Review in 1965, are “new connections between images,” new ways of viewing an old text and discovering hidden or obscure messages within. And it allowed his work to place at least one foot in the real world.

Lovecraft also had a way of meshing reality and fantasy in his work. But in his mind, it wasn’t magic — it was a confidence trick. In a letter from 1934, he explained to the writer Clark Ashton Smith his belief that “no weird story can truly produce terror unless it is devised with all the care and verisimilitude of an actual hoax.” Often, his stories were structured not as fiction but as essays or news accounts: “Just as if he were actually trying to ‘put across’ a deception in real life.” The results were stories that to this day still has people wondering if there isn’t an element of truth to them. And around the country, people had fun with it — reports started turning up of entries for the Necronomicon in card catalogs in university libraries and mail order book catalogs. Lovecraft once even admitted: “I feel quite guilty every time I hear of someone’s having spent valuable time looking up the Necronomicon at public libraries.”

“The deepest levels of the unconscious mind where the Ancient Ones dwell must inevitably surface for all to see.”

There’s a basic template that’s considered “Lovecraftian,” although it was never actually used by Lovecraft — rather, it was popularized by later writers of the Lovecraftian tradition. In these stories, which are often supposed to be diary entries or essays, the main character discloses the fact that he’s learned a secret, or uncovered some particularly powerful form of magic. Although there are plenty of indications that things are getting out of hand, the writer continues to experiment, until he realizes that he has unleashed a monster — which, at that point, kills him. End of story.

As a result, you get a peculiar lesson: there are things that simply aren’t meant to be known. Knowledge is dangerous, deadly even. It’s interesting to note Burroughs’ reaction when he stumbled upon a real life Necronomicon: “The deepest levels of the unconscious mind where the Ancient Ones dwell must inevitably surface for all to see,” he wrote. “This is the best assurance against such secrets being monopolized by vested interests for morbid and selfish ends.”

In other words, Burroughs — as a man who believed in magic, and who was in awe of it, believed that the greatest danger posed by the Necronomicon was that it might be monopolized by a select few. In other words, Lovecraft thought we could learn too much, while Burroughs knew that the real danger is that we know too little.

It was fun

At this point, you’re probably asking yourself who this Simon character is exactly, and why anyone would put stock in his book.

As far as the Simon Necronomicon is concerned, you’d be hard pressed to prove that it’s actually an ancient magical text. The fact of the matter is that there is no record of a Necronomicon existing prior to H.P. Lovecraft’s invention, and the manuscript that Simon says he received from some rare book thieves is nowhere to be found. (The thieves, Huback and Hapo, are real, however. But there’s nothing to tie them to this caper. It looks like Simon brought a real news item into his story to add verisimilitude — just as Lovecraft would have, if this were one of his stories.)

The most common theory is that the role of Simon is being played by The Dark Lord author Peter Levenda. According to a brief bio from the Coast to Coast AM website, Simon “has appeared on television and radio discussing such topics as exorcism, Satanism, and Nazism,” as has Levenda. In fact, when Simon appeared on the talk show, he attempted to disguise his voice by speaking through some sort of audio effect that lowered the pitch a couple of steps. When I played the audio file on my computer and pitched it back up using Ableton Live software, the unmasked Simon’s voice clearly sounded like that of the Peter Levenda I interviewed earlier this year. Most tellingly, if you do a record search at the US Copyright Office website, “Peter Levenda (Simon, pseud.)” appears as the copyright owner on two of Simon’s books (The Gates of the Necronomicon and Papal Magic).

“The Necronomicon should be in the hands of the people.”

I asked Alan Cabal, a former child actor, who — in addition to playing “Stanley” on one memorable episode of the Patty Duke Show — worked at The Magickal Childe “off and on” from 1978 until the early 1990s, whether Simon and Levenda were in fact the same.

“Levenda is such a fuckin’ snake, man,” Cabal replied. “He’s doing lectures as Simon at The Magickal Childe. He’s doing workshops as Simon. And then all of a sudden, he decided to not be Simon.”

When I asked Levenda to respond, his answer was short and to the point.

“No,” he said. But “I’m perfectly flattered to be confused with Simon.”

When asked by Ian Punnett on Coast to Coast AM why he released the Necronomicon, Simon’s answer mirrored that of Burroughs. “The Necronomicon should be in the hands of the people,” he told host Ian Punnett. “I think we as people have been betrayed by our leaders in many different areas. I don’t know if we can trust them to protect us, quite frankly.”

But there’s another motivation for having produced this hoax-Necronomicon, and it’s one that I can’t say I disagree with.

“It was fun,” Peter Levenda said on a recent Thelema Now! podcast. He was talking about the New York occult renaissance of the 1970s and 1980s in general, a scene that flowered in that brief moment between Vietnam and the conservative counter-revolution in the 1980s where people thought that they could inject some positive magic into everyday life, a sense of adventure that perhaps was overshadowed by the heaviness of the times — and of the Necronomicon.

“There was this window of opportunity,” he continues looking back on the occult resurgence of the 1970s, when “we wanted to show that this is not scary stuff. It could be powerful, it could be mind-altering, it could change your life. But it was not dangerous, it was not going to kill you. And that’s what we were trying to promote.”

I recently paid a visit to the former location of The Magickal Childe. Herman Slater died of AIDS in 1992 and his store folded soon after. In its place there’s now a restaurant called Sala One Nine. It was a quiet evening (they ended up closing at 11:00PM) and the place was low-key, dimly lit. I tried to get a sense of what was there once before, of the rich history of the location, but I couldn’t. It’s just another fine dining establishment in a city that’s feeling pretty one-dimensional these days. Before I left, I spoke to the restaurant’s manager. I wanted to know if she knew anything about The Magickal Childe.

“Oh yes,” she said. “I see them all the time.”

Him? Them? I couldn’t quite hear what she was saying. So I asked, “What do you mean? People come in often and ask about the shop?”

“No,” she replied. “I mean the ghost!”

Apparently, she felt it the first time she entered the space. This presence. I didn’t notice it, but then again I could be run over by a truck and I might not notice (strike it up to my journalist’s keen sense of situational awareness). The ghost never bothers her, it turns out — but none of the men working there will be in the store alone, after hours. The ghost won’t leave them alone.

Why is she off limits, while the men get so much grief?

The manager says, with a laugh: “It’s a gay ghost!”

The world of H.P. Lovecraft might be a bleak one, but at least Herman Slater’s still having fun. Wherever he is.

Illustrations by Karina Eibatova