If the last decade saw superhero movies edging towards the overwrought and self-important, The Amazing Spider-Man 2 may go too far in returning them to their silly, comic-bookish origins. While an improvement over its 2012 predecessor, director Marc Webb’s follow-up is populated with fan service and franchise bait, but leaves its actors — and the audience — foraging for anything resembling a human connection. The result is camp without conviction; a Batman & Robin-style scenery chewer in a Batman Begins era.

Andrew Garfield returns as Peter Parker, a high school senior who’s late for his own graduation, including the commencement speech of his girlfriend Gwen Stacy (Emma Stone). It’s all because of his responsibilities as Spider-Man, which in this case include stopping Russian mobster Aleksei Systsevich (Paul Giamatti) from stealing vials of something or other. Peter is struggling to reconcile his feelings for Gwen with the promise he made to her late father: that he’ll keep her away from his life of crime fighting. He eventually insists they break up, only to have their paths cross after Gwen discovers her colleague Max Dillon (Jamie Foxx) has been transformed into the supervillain Electro.

Old friends become enemies

As Peter contends with this threatening new adversary, he reconnects with his old pal Harry Osborn (Dane DeHaan), who’s become head of the mega-corporation Oscorp in the wake of his own father’s death. Desperate for a cure to the degenerative — and hereditary — disease responsible, Harry discovers that Peter’s father developed a pioneering serum that could save his life. Spider-Man appears to be the beneficiary of the serum, but when Peter refuses to put Harry in touch with the crime fighter the two friends become enemies, and Harry teams up with Electro to take his revenge.

Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 2 was released 10 years ago this summer, and it’s impossible to avoid comparisons between Webb’s film and what many regard as one of the best superhero movies ever made. The romantic relationships are nearly identical in both films, though Gwen is a decidedly better companion for Peter than Kirsten Dunst’s dream-girl Mary Jane was. But here his wishy-washy attitude is even more exasperating, the entirety of their problems boiling down to the amount of guilt he feels about his promise to her father in any given scene. Until it’s time for Gwen to become a pawn or damsel in distress, watching her and Peter interact feels like sitting through a documentary about two indecisive teens — and it’s exactly as tedious as that sounds.

Good actors can’t save bad writing

The good news is that Garfield and Stone give this superficial complexity every ounce of energy they’ve got. But they can’t out-act bad writing, and screenwriters Alex Kurtzman and Roberto Orci (Transformers, Star Trek) give them nothing but soapy angst to explore. Still, that’s more dimensionality than the supporting characters get, who as a whole resemble the sort of over-the-top cartoonish villains the genre has spent decades trying to live down.

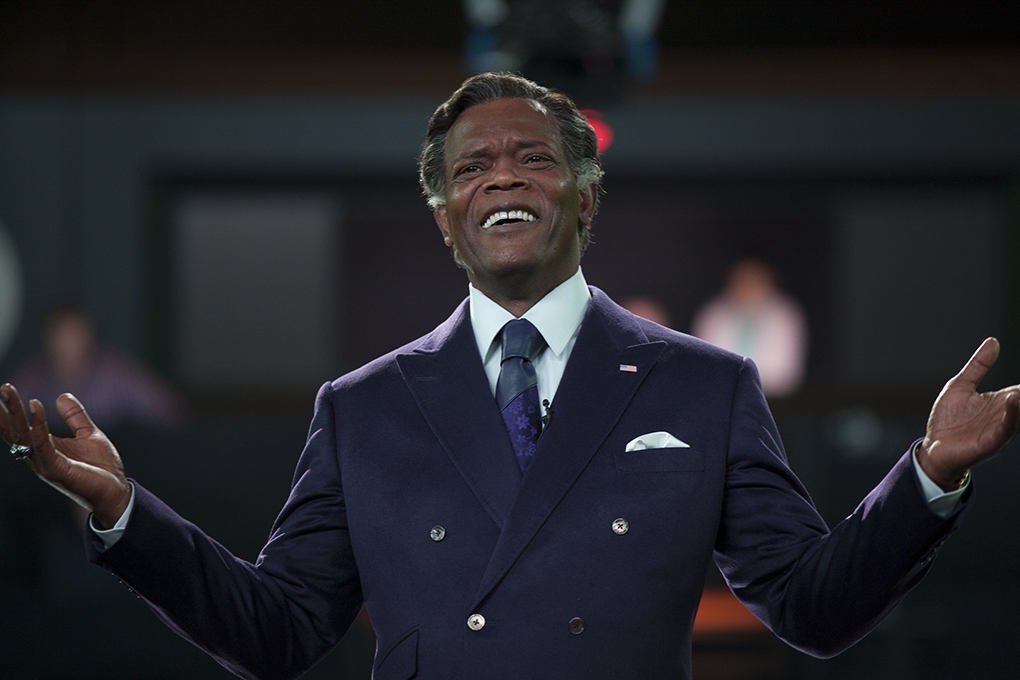

The problem with Electro isn’t that he looks like Arnold Schwarzenegger’s Mr. Freeze, but that he was conceived like Jim Carrey’s Riddler: a “brilliant,” socially awkward doormat who perceives every compliment or slight as if it’s a life-changing event. Dane DeHaan throws himself into playing Harry Osborn with abandon, regurgitating exposition with sincerity and transforming Harry’s parental neglect into an almost believable sense of rage. But if James Franco’s portrayal in the first Spider-Man movies lacked enough internal torment, DeHaan exudes too much, never once seeming like the young man he’s supposed to be — even one coming to terms with the responsibility of a billion-dollar company and a potentially terminal disease.

That said, the over-the-top characters do complement the enormous technical ambition of the action scenes. The film’s centerpiece takes place in Times Square, cleverly using its 360-degree video screens as the eyes of the world that Electro so desperately wants to impress, and the eventual showdown is genuinely impressive. Notwithstanding the fact that his powers make him feel like a junior version of Watchmen’s Dr. Manhattan, Electro gives Spider-Man a challenge that is genuinely exciting and even dangerous.

The problem is that by the time The Amazing Spider-Man 2 reaches its finale, the action has become so polished and joyless that you just want it to be over with. There are painfully few applause-worthy moments for a movie intended to be a crowd-pleaser, as the filmmakers seem determined to get to the end of the story out of dutiful obligation to the source material rather than passion or interest. Of course, even that level of broad good guys-vs.-bad guys adventure will undoubtedly keep burgeoning superhero fans entertained. But for anyone who’s enjoyed watching the genre grow and mature over the last decade, Webb’s sequel feels like a cautious reminder: we can go back to the days of lame puns and larger-than-life bad guys, but we probably shouldn’t.

The Amazing Spider-Man 2 is now playing internationally. It opens in the US on Friday, May 2nd. All images courtesy of Columbia Pictures.

<!--document.write('');// -->

{ "@context" : "http://schema.org", "@type" : "Review", "author" : { "@type" : "Person", "name" : "Todd Gilchrist", "sameAs" : "https://plus.google.com/105857324336838346894" },"datePublished" : "4/30/2014","description" : "If the last decade saw superhero movies edging towards the overwrought and self-important, The Amazing Spider-Man 2 may go too far in returning them to their silly, comic-bookish origins.","itemReviewed" : { "@type" : "Movie", "name" : "The Amazing Spider-Man 2", "sameAs" : "http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1872181/", "datePublished" : "5/2/2014", "director" : { "@type" : "Person", "name" : "Marc Webb", "sameAs" : "http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1989536/?ref_=tt_ov_dr"},"actor" : [ { "@type" : "Person", "name" : "Andrew Garfield", "sameAs" : "http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1940449/?ref_=tt_cl_t1" }, { "@type" : "Person", "name" : "Emma Stone", "sameAs" : "http://www.imdb.com/name/nm1297015/?ref_=tt_cl_t2" } ]},"publisher" : { "@type" : "Organization", "name" : "The Verge", "sameAs" : "http://theverge.com"}, "reviewRating" : { "@type" : "Rating", "worstRating" : 1, "bestRating" : 5, "ratingValue" : 2}, "url" : "http://www.theverge.com/2014/4/30/5666786/the-amazing-spider-man-2-review"} ]]>

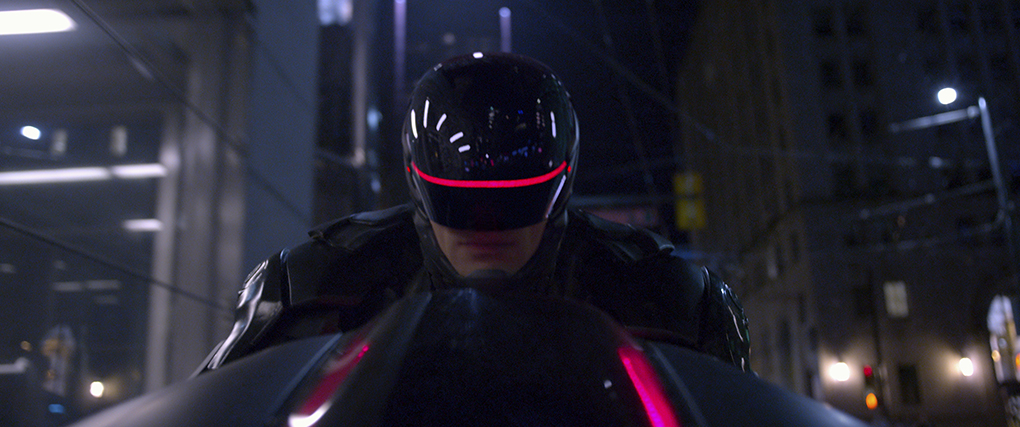

Joel Kinnaman and Gary Oldman in RoboCop. (Columbia Pictures and MGM Pictures)

Joel Kinnaman and Gary Oldman in RoboCop. (Columbia Pictures and MGM Pictures)